COVID-19 Tales

Introduction

COVID-19’s arrival brought unprecedented times to the UIC College of Pharmacy, challenging the ways students learn, researchers progress, faculty teach, and clinicians practice. Despite a fluid, fast-changing public health situation, the college remained steadfast in its mission to educate, to conduct cutting-edge research, and to provide innovative patient care.

In a series of first-person essays, members from across the college community—administrators, faculty, clinicians, and students alike—detail the novel coronavirus’s impact on their lives and how they worked to adapt amid trying circumstances. Shining with resolve and purpose, their stories underscore the persevering spirit so engrained in the college’s DNA.

Dr. Glen Schumock

Dr. Glen Schumock

A member of the UIC College of Pharmacy faculty since 2000, Glen Schumock succeeded Jerry Bauman as dean of the college in January 2018.

It might come as no surprise to you, but for most of my first two years as dean, it felt like I was swimming upstream. As much as I thought I was prepared for this role, the reality of it was the opposite. The huge responsibility and many moving parts were disorienting. However, by the end of 2019, I felt that I understood the scope of the job and had learned to lean on a highquality team of associate deans, department heads, and many willing faculty and staff across the college. With most of the building blocks in place, I walked into 2020 more comfortable and confident in my role.

Then, COVID-19 appeared and changed everything.

Like most, I followed COVID-19’s emergence overseas. Still, I had no idea of the impact the virus would have on all of us. While I was visiting my mother in the Pacific Northwest in February, metro Seattle reported its first COVID-19 cases. That’s when this virus’s potential impact started to hit home.

Things happened quickly after that. With news coming in every day about how the disease might affect us and how other universities were preparing, it became clear that life would need to change. And that brought a flurry of activity that demanded constant concentration, focus, and sustained effort that continues to this day.

To gather input, make decisions quickly, and implement changes, we formed a College of Pharmacy Emergency Response Team comprising associate deans, department heads, and other key leaders. The group met daily for several months to address the myriad

COVID-19’s arrival brought unprecedented times to the UIC College of Pharmacy, challenging the ways students learn, researchers progress, faculty teach, and clinicians practice. Despite a fluid, fast-changing public health situation, the college remained steadfast in its mission to educate, to conduct cutting-edge research, and to provide innovative patient care. In a series of first-person essays, members from across the college community—administrators, faculty, clinicians, and students alike—detail the novel coronavirus’s impact on their lives and how they worked to adapt amid trying circumstances. Shining with resolve and purpose, their stories underscore the persevering spirit so engrained in the college’s

challenges created by COVID-19, and we found ourselves revisiting decisions and pivoting to new information and policy changes at the campus, city, state, or federal level on a near-daily basis. Even now, we continue meeting several times a week. That group has been invaluable to helping the college successfully navigate this crisis.

The pandemic made us reevaluate everything. It reminded me of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs—a pyramid-shaped model of human needs I first learned about in high school psychology. At the base of the pyramid sit basic functions like safety and security. We needed to make sure those basic functions were met to survive this crisis. Are pharmacy staff in the hospital and clinics working in safe environments? How do we get faculty the resources they need to quickly convert to online courses? Who checks the research specimen refrigerators or other equipment in our labs? Is the building secure with limited staffing? These and many other questions weighed heavily on me and our leadership team.

I think sometimes people assume the dean clutches some privately held information that shapes and informs the decisions we make. I can assure you there is no such top-secret file—or Google drive. Even so, I understood people needed reassurance and guidance. We tried to provide this through communications— e-mails, town hall meetings, and social media. The notion that there can never be too much communication was evidently clear.

I also learned that while people needed information, they also wanted distractions—ways to take their minds off the crisis and onto something more “normal.” I felt this personally and found comfort in conversations with my fellow deans across UIC and at other colleges/schools of pharmacy. I was pleased to see so many organic efforts at this being taken by our students, faculty, and staff as well—efforts to boost morale and create positivity. Many of these were occurring on social media, and so I tried it myself with my “Yoga Everywhere” videos—and I’m clearly terrible at yoga. Doing poor yoga poses at various spots across the college generated at least one “like” from my college-aged daughter.

I found inspiration, motivation, and perspective in our college community. People across the college rose to the occasion. Faculty and students adapted to online learning. Pharmacists reported to work on the frontlines at our sites. Researchers continued pursuing scientific work, including some investigating treatments for COVID-19. Staff persevered amid the many challenges of remote work.

Through it all, we completed the spring term and our P4 class graduated on time. And though we missed the traditional commencement ceremony, the virtual celebration was fun and appreciated by our students.

By June, we reopened our research labs, albeit with a range of controls to keep people safe—installing hand sanitizer stations, removing furniture, and creating lab schedules among the many COVID-prompted interventions.

It has been and continues to be overwhelming to see people sacrifice to sustain our teaching, research, and service mission and to do so without complaints. I am humbled—truly, sincerely humbled—to be in a position to watch this happen, to be a part of it, and to serve the people who are putting our mission into action. It awakened a reality that might be too often underappreciated: our people drive UIC’s status as one of the world’s top pharmacy schools. This crisis confirmed that.

And now, we march ahead.

Navigating uncertainty remains our most significant challenge and we must balance reestablishing some normalcy with ensuring the safety of our students, staff, and the entire college community. We have crafted plans—and numerous contingency plans—addressing the myriad interrelated pieces necessary to ensure a safe environment as well as the ever-looming threat of COVID-19’s aggressive resurgence. Classrooms that once held 175 students now hold 40 to accommodate social distancing, while class schedules are staggered to avoid crowds. In the age of coronavirus, it is difficult to plan even a month ahead. Still, delivering a quality education regardless of the circumstances remains an unrelenting priority.

This crisis has sharpened us, and I believe we are a stronger, more resilient, more purpose-filled college today than we were at the start of 2020. We are more advanced in our use of technology, committed to exploring novel ways of expanding access and sharing knowledge. We have a heightened sense of our duties as clinicians while our healthcare partners and the public at large increasingly recognize the unique skillset and value pharmacists bring to patient care. We more acutely understand our important role as innovative researchers. We are more aware of our surroundings.

From the throes of crisis, I carry two unshakable thoughts into the future. One, our college is a dynamic, robust institution filled with world-class people committed to our mission, and two, I am beyond grateful and proud to be part of it.

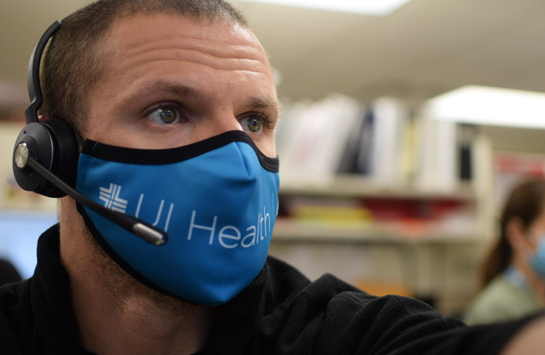

Andy

Dr. Andy Donnelly

Andy Donnelly has served as the director of pharmacy at the University of Illinois Hospital & Health Sciences System since 2002. As pharmacy director, Donnelly, who is also the college’s associate dean for clinical affairs, oversees the central hospital pharmacy and its four satellite locations, its seven outpatient pharmacies, and the clinical pharmacy services provided to patients in the hospital and clinics.

In my four decades as a pharmacist, I never experienced anything like COVID-19. Here was a new virus that was not going away. None of us knew how to best treat it—or if we even could. The drugs that we did have produced mixed results. The stress felt by everyone was palpable, and we knew early on this would be a tough, lengthy battle.

Monitoring the happenings overseas in the first months of 2020 made me aware of the potential magnitude of this virus. Yet, COVID-19 far surpassed my expectations, and I certainly never envisioned what became our reality once the first patient arrived at our hospital on March 13: a medical intensive care unit soon filled with critically ill patients; substantial drug shortages; and an intense, still-ongoing effort that has demanded flexibility, teamwork, and vigilance to ensure patient care and staff health, which is something we take very seriously.

COVID-19’s impact was swift and significant, forcing us to react and prepare as best as possible for the expected rapid influx of patients. As our number of COVID-19 patients increased, we had to convert several units to COVID-only patient care areas and expand the number of MICU beds, hopeful those changes would provide the necessary capacity. Drug shortages, meanwhile, were immediate and severe. We needed medications such as fentanyl, midazolam, and neuromuscular blocking agents for the ever-increasing number of intubated COVID-19 patients, yet had difficulty obtaining those medications in the timeframe needed and in the quantities desired. This forced us to develop guidelines and algorithms to ensure that the medications we did have were used on those patients needing them the most with alternatives available for those less severely ill.

While we continued to provide the most thorough care possible, the unrelenting drug shortages weighed heavily on me and many members of my leadership team. As pharmacists, one of our primary responsibilities is to provide medications for our patients, and we wanted to accomplish that. The pandemic’s firm grip on the nation and the world, however, tested our ability to fulfill that mission and demanded creativity, planning, and resolve.

Then, as Easter weekend approached, hospital administration asked us to be ready for upwards of 100 COVID-19 patients. Such projections intensified an already stressful work environment. I was concerned about having enough medications for a patient load of this magnitude and what this could mean for our staff charged to take care of these patients.

While those forecasts never came to bear, a heavy COVID-19 case load remained throughout the spring. My focus remained on having enough medications to meet our patients’ needs, ensuring that our patients received the best drug therapy possible, and keeping my staff safe and healthy. Eleven-plus hour days became the norm, and save Easter and Memorial Day, I was at the hospital working every day from the middle of March well into June.

Throughout the pandemic, I have been proud of our pharmacy team’s resilience and commitment. In a demanding and draining environment that required their best effort, they delivered that each and every day. They overcame obstacles thrown before them and kept patient care top of mind. Numerous process changes had to be made in our outpatient pharmacies to allow our staff to safely fill and dispense prescriptions as well as to counsel our patients, including developing a special workflow for our COVID-19 patients. Process changes were also implemented in our central and satellite pharmacies that enabled our staff to carry out services as close to pre-COVID levels as possible. Our clinical pharmacists continued to follow patients in the clinics and hospital, either via telehealth or by being physically present on patient care units, as was the case for those covering the MICU.

As the number of COVID-19 patients dropped in June, the organizational mindset shifted from surviving COVID-19’s initial surge to “reopening” the hospital and clinics. Surgery and procedure volumes began to work their way back to pre-COVID numbers, while clinics balanced the use of telehealth and on-site appointments.

The push to reopen the hospital brought an added layer of complexity to our pharmacy operations since many of the drugs used in the operating room and procedure areas are the same ones needed to treat intubated COVID-19 patients. To ensure we could service all patient needs and support the hospital’s reopening strategy, we created our own backstock of key medications. We built a two-week supply for our COVID-19 patients based on historical use alongside a five-day supply for our operating room and procedure areas. Maintaining such inventory levels demanded some creativity in storing the excess supplies, including lining the College of Pharmacy’s basement with multiple pallets of CRRT solution.

As we move forward, we do so mindful of COVID-19’s ongoing presence and the threat of additional surges. We need to remain careful, focused, and vigilant, especially in monitoring our medication supply and addressing inventory levels with a critical eye on the data. We need to keep our staff safe and healthy by continuing to provide appropriate personal protective equipment, by practicing social distancing, by ensuring high-touch areas in our pharmacies are routinely cleaned, and by installing contact barriers between our patients and staff where needed and that our staff remained as safe as possible. We persevered. We cared. We endured.

Given everything COVID-19 threw at us, that’s no small feat. In fact, it’s a lively testament to the unshakable vigor of our pharmacy department and its people.

Vicki

Dr. Vicki Groo

A clinical associate professor in the Department of Pharmacy Practice, Vicki Groo has served as a clinical pharmacist at the UIC Heart Center since 2004, a role in which she oversees experiential learning for both PharmD students and residents.

As the calendar shifted from February to March earlier this year, I knew little of COVID-19 and, truth be told, stood naïve to its potential impact. Like many others, I discounted this virus’s ability to wash over us and rattle our daily lives.

By March 9, however, my miscalculation became apparent.

That day, the American College of Cardiology (ACC) cancelled its annual meeting scheduled to begin on March 28 in Chicago. (Just four days prior, it’s worth noting, the ACC announced it would proceed with the event as planned, a nod to the fast-changing nature of things as COVID-19 penetrated the United States in rising numbers.) As the ACC moved discussions and content online, I listened to doctors from China share poignant firsthand accounts of their experiences battling COVID-19. Those tales awoke me to the seriousness of this disease, while around-the-clock reports of cases exploding in European nations, rising fatality numbers, and travel restrictions confirmed the virus’s far-reaching impact.

The subsequent days, weeks, and months required adaptability as my work on both the academic and clinical side at the college shifted at a rapid pace. New rules. New schedules. New communications platforms. New work environments. Realizing I could not be stuck in my ways—changes were being thrust upon me whether I was ready or not, whether I liked it or not— I adopted a go-with-the-flow attitude.

With word that classes would be moving online, I transferred documents and course materials over to the cloud. Having never taught online before, I explored different ways to present lessons and recorded lectures in front of empty classrooms, a truly odd experience of talking into vacant space after years of lively face-toface engagement with my students. Without a home office and with my forced-to-work-remote husband taking over the dining room, I commanded a card table in our home’s backroom. When I wasn’t trying to piece together class lessons or clinical projects on that card table, I rolled up a gray tablecloth and tackled different 500- or 1,000-piece puzzles—a different mental exercise to escape, if only temporarily, the escalating tension this pandemic delivered.

The biggest challenge I encountered on the academic side came with the recitation sections in April. With that being tackled online, we lost the individual group dynamic and interaction so central to making that annual rite of passage a rich learning experience. Still, those students showed resiliency and flexibility, qualities I am certain will prove valuable as they progress in their careers.

At the Heart Center, where I am accustomed to seeing a full slate of patients three days a week, operations changed drastically.

During the week of March 23, only two of six Heart Center patients arrived for their appointments. The following week, no one showed. We consolidated into teams and reassessed every patient on the schedule, moving follow-up appointments back. As a clinician, the no-shows concerned me as did delaying appointments. As so many of our patients are already in a precarious health state, I wondered about the potential downstream effects of people delaying their healthcare. Might people be sicker than expected when we finally do see them back in the clinic? Here in the fall, this concern continues swirling around my mind.

We did, of course, introduce telehealth into the mix at the Heart Center. Through our transition of care service, we typically see patients within seven days after their hospital discharge. Because of COVID-19, we began visiting with these patients remotely. While telehealth has its definite appeal, and I am glad our trainees are receiving early exposure to this likely here-to-stay technology, I worry that we miss things in the digital world that we would otherwise notice in a face-to-face visit.

For example, a resident pharmacist charged to follow up with some of our high-risk patients and to perform transition of care reviews found one patient who had been without her water pill for five weeks and gained 15 pounds as a result. Had we seen this patient as scheduled, we would have caught this. With telehealth expected to remain for the foreseeable, albeit cloudy, future, my colleagues and I will continue to explore ways to be more thorough and comprehensive with care. If this is our reality, then we want to thrive in this environment.

As the Heart Center’s satellite clinic remains closed, we must continue to adapt on the training side as well. We are regularly integrating P3 and P4 students as well as PGY1 and PGY2 residents into our clinic, but how do we fit them all in and deliver a beneficial learning experience, especially with a limited number of patients even coming into the clinic? Here again, we continue to adapt, pivot, and evolve. In the Heart Center’s pharmacy clinic, which is fully telehealth, I have trainees listening in on a group video chat with patients during the first week before leading calls during subsequent weeks.

While things that typically take place in an exam room are now happening via a multimedia connection, we remain eager to unlock ways to incorporate more trainees into our clinic amid social distancing guidelines. We understand how powerful direct patient access and interaction with other healthcare providers can be for our trainees, and those in-person experiences are something we want to provide whenever safely possible. As much as we can accommodate that in a prudent way, we will.

COVID-19 has demanded adaptability with uncertainty being the only sure-fire certainty. Despite encountering new guardrails, we continue to navigate within any newly set boundaries to serve our students and our patients. That, of course, remains our mission in good times and bad.

Scott Benken

Dr. Scott Benken

A clinical associate professor in the Department of Pharmacy Practice and clinical pharmacist in the Medical Intensive Care Unit (MICU) at the University of Illinois Hospital, Scott Benken rounds with the MICU team recommending medications for patients, takes on residents in service, and teaches research-related courses in critical care.

I won’t soon forget Friday the 13th.

That morning—Friday, March 13—I received an e-mail from my children’s school about a potential closure. That was my first touchpoint with COVID-19. Like many others, I heard the reports of COVID-19 bubbling overseas and then saw it capture more and more national attention throughout February and into March. But until that March morning, the virus seemed a distant worry.

That afternoon, our MICU received its first COVID-19 patient: a relatively healthy young man only two years older than me. I was stunned, not only that this novel virus, which I had previously only known through news reports and occasional chatter with colleagues, had officially infiltrated my life, but that it had invaded someone so like me. That reality jarred me, signaling that COVID-19 was here, unlikely to disappear anytime soon, and even more serious than I ever imagined.

Within two weeks, our MICU was overflowing with COVID-19 patients, an influx that quickly became so great that we converted the pediatric unit into a second MICU. The depth and breadth of patients and the severity of this virus shifted every aspect of the MICU. Save rounding with the team, no aspect of my work was “typical.”

The MICU, an inherently complex environment, became even more complex as we were overrun with critically ill patients, breathing machines, and drug shortages that forced us to implement nontraditional practices. We worked tirelessly to come up with treatment plans and alternative medications. Can we use this? How do we get it? To ensure a normal flow of medications and address drug shortages, you need to be forward thinking and discover solutions. Our team and pharmacy department did that with tremendous thoughtfulness and strategy.

Amid the early COVID-19 onslaught, we continued to incorporate pharmacy residents. The nature of the medical ICU is that residents need to be on the floor. Looking back upon those early weeks battling COVID-19, the residents’ presence helped to keep us from drowning.

Name an emotion and I encountered it this past spring. At times, I felt defeated and stretched to my max. I saw people near my own age confront this invisible enemy and die, while others passed after weeks of futile medical effort. It reminded me of the frailty of life and offered an appreciation for each breath. At one point, I had to quarantine for 72 hours. While I tested negative for the virus, that reality-check situation forced me to pause. I have a wife and three children under the age of six. The thought of potentially infecting them stirred angst and pushed me to be extra diligent, careful, and focused upon my return to the MICU.

At times, the outpouring of love, support, and positivity directed at our MICU team as well as those success stories of patients pulling through and walking out of the hospital proved uplifting. We needed those little moments of celebration amid disheartening times, especially as we saw more COVID-19 patients expire than leave our doors. While the MICU is no stranger to end-of-life events, losing such battles on a daily basis

tested our hearts and minds. During such a merciless, wearing struggle, my faith provided perspective, drive, and comfort.

By mid-May, about eight weeks into this fight, we achieved some stable footing. Though our COVID-19 patient count remained high, we had developed a better sense of the disease process and patient care. We had also worked with purchasers and buyers to address our drug shortages, even creating our own stockpile. Those combined efforts sparked some relief and minimized anxiety. By July, COVID-19 patients no longer dominated our MICU. We had survived the storm, but hesitated to relax, especially as COVID-19 cases jumped in states across the country, including Illinois, throughout the summer.

Today, the big-picture questions fill my mind. Will we ever get back to normal? What does normal even look like? Yes, we know how to better care for patients and have addressed drug shortages, but COVID-19 continues lurking around us. Will it strike again? When and how severe? The ongoing threat looms and it’s overwhelming to think about additional surges.

COVID-19 exposed cracks in our healthcare system, including our MICU operations. We had to expand the MICU and borrow staff from elsewhere. Relying heavily on residents and cross-coverage provides a temporary, but ultimately unsustainable, solution. Moving ahead, I see personnel as the biggest challenge we face. Are we able to make an investment in staff so we are not just getting by, but can flex as things ebb and flow? That’s something I hope we continue to address.

To be certain, COVID-19 sparked some positive takeaways, too. Our cohesiveness from a departmental standpoint has never been higher. The pandemic forced us to reevaluate protocols and guidelines for our MICU patients and things we do from a systems standpoint. We made progress building out electronic systems and created order sets that bring new providers quickly up to speed. We optimized the way we care for patients in the MICU, and with more providers, more patients, and an aggressive disease, this needed to happen. We’re a better, stronger unit moving forward because of that.

From that Friday the 13th and throughout the spring and then into the summer months, clinical pharmacists remained an ongoing presence in the MICU and stood on the frontlines of care. Oftentimes, I encouraged the pharmacy residents to note that and to recognize the important, vital role we play in patient care. I hope that motivated and inspired them because we need competent, engaged pharmacists now more than ever.

COVID-19, after all, won’t be the last crisis we face.

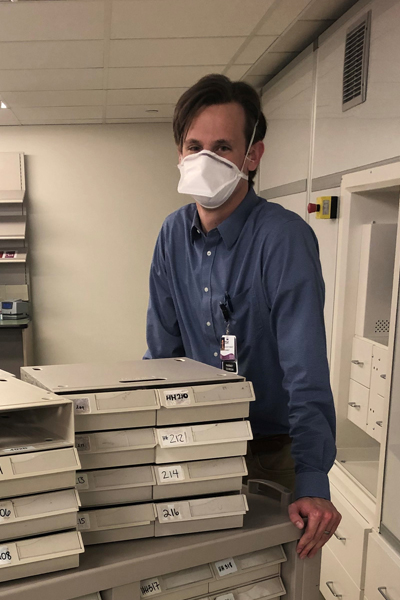

Federle

Dr. Michael Federle

Michael Federle is a professor in the Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences and director of the Center for Biomolecular Sciences. His lab investigates quorum sensing, which is how bacteria coordinate gene expression and behavior across microbial populations through chemical communication.

I compare COVID-19 to a slow-motion train wreck. Initially, I thought the derailment would be a modest disruption. “Only a week or two,” I told myself. It’s clear now my optimism exceeded the reality.

In March, active lab work came to a near-complete standstill as we were forced to work remotely. Without access to our lab, we adjusted to keep our brains engaged in progress and to sustain different research projects as best as possible.

We shifted to interpreting on-hand data sets and pursuing grants. We wrote, including making substantial headway on numerous manuscripts. We read, using the time to get deep into the literature on our own projects and to consider new efforts. We had some forwardthinking students begin learning bioinformatic and statistical programming languages, which are powerful skills in the age of big-data science.

I, and certainly my colleagues, were as busy as ever with meetings, grant reviews, paper reviews, editorial work, student thesis committees, administrative meetings, and trying to keep our teams motivated and challenged. In the interest of reducing anxiety and providing encouragement, I arranged one-on-one virtual meetings each week with members of my lab team, while we also connected virtually as a group through weekly happy hours. I felt for the students and postdocs and this disruption to their careers.

But as the weeks passed, I could sense simmering unease and digital fatigue, especially as the days became consumed by managing e-mail and rushing to the next virtual meeting. We’re a hands-on, experimental bunch eager to interact with each other, excited to pursue new ideas and advance science. Not being in the lab zapped our spirits.

Fortunately, we began a progressive process of reopening the research labs in late June, albeit with a litany of accommodations from maintaining social distancing to working in shifts. The opportunity to return to the lab, to resume hands-on research and regenerate that stream of productivity, has been invigorating, though it has not been business as usual. We are doing our best within the constraints, simply grateful we’ve been able to pursue quasi-normal operations.

While I try to keep fear from consuming my mind, the future does concern me. So many of our students and trainees face substantial questions about current projects as well as their career trajectory. Collaboration and idea-sharing, so important to scientific research, have been curtailed. We’re not working freely alongside one another in the lab, attending conferences, or welcoming visitors. And while there has been an overall surge in scientific papers being submitted, I wonder if the work is as thorough as it otherwise would be.

The coronavirus has hampered science, and it could take some time to see progress restored. I do believe science and pharmacy can emerge better from these challenging times. More resilient. More determined. More focused. I place my faith in that and sincerely hope that becomes a positive result of these unprecedented times.

Kyle

Dr. Kyle Mork

Over the last decade at the University of Illinois Hospital & Health Sciences System, Kyle Mork has graduated from float pharmacist to clinical pharmacist to his current position as ambulatory care pharmacy coordinator. At the Wood Street pharmacy, Mork, under the supervision of Kit May, oversees pharmacy staff and pharmacy operations.

When I reflect on the impact of COVID-19 to my role in the pharmacy world, a single word leaps to mind: adaptation.

As the novel coronavirus emerged from distant threat to present reality and demanded operational changes, as civil unrest shuttered local pharmacies, and as new information and recommendations about COVID-19 emerged, our Wood Street pharmacy adapted in a seamless way. That it did so remarkably well stands a credit to the professionalism and focus of our staff.

Immediately upon COVID-19’s confirmed appearance in the Chicago area, we split our staff into on-call and on-site teams. That way, our entire squad would not be compromised by one positive test. One after another, we integrated new procedures, policies, and environmental changes into our workflow: installing a sneeze guard to separate patients from pharmacy staff; requiring face masks for staff and offering face coverings to visitors; capping the waiting room capacity at four people; training pharmacists on how to temperature screen patients in a contactless method. All of this as our script volume jumped as the hospital became more efficient with discharges to accommodate the COVID-19 wave.

Throughout the spring and into the summer, we continued adapting and evolving our actions to protect staff and patients. We planted a staff member at the front of the pharmacy to screen all visitors, accelerated our mail order dispensing to minimize in-store visits, and moved select staff to alternative work sites on campus.

There is no end in sight to the precautions we are instituting, and we plan to indefinitely operate with patient and staff safety as our foremost priority, even as typical hospital operations resume and our volume rises above pre-COVID levels. As this virus has not disappeared, neither can our vigilant response to it.

While COVID-19 certainly triggered some unease, the pandemic also drove us to become a more focused, efficient operation. For example, large brainstorming sessions among the management team have given way to more concentrated meetings. We now set our agenda, hammer out a plan, and go.

Time and again, we adapted, taking a barrage of challenges and changes in stride to serve our patients. When many local pharmacies proactively closed or temporarily ceased operations after looting tied to May and June’s social unrest, our Wood Street pharmacy remained one of the few pharmacies open on the city’s near west side. We established ourselves as the pharmacy that did not close, and that brought a stream of new patients into our doors.

The constant changes and ongoing grind could have decimated our spirit as pharmacy professionals. Instead, I watched these times inspire and empower our team. We were essential workers on the frontlines, and individually as well as collectively, we embraced that responsibility and executed with a commitment to our patients and to one another.

Chris

Dr. Chris Schriever

Chris Schriever is a clinical assistant professor at the UIC College of Pharmacy’s Rockford campus, where he chairs the Infection Control Committee and precepts pharmacy and advance practice students.

I like things neat and orderly, but those preferences clash with the innate fluidity a global pandemic like COVID-19 brings. Since March, unease has hovered over my life, a result of swirling uncertainty about what I would be tasked to do and when.

With Rockford lagging about two to four weeks behind the Chicago area in terms of COVID-19 cases, the Winnebago County Health Department, concerned that local hospitals could be overwhelmed by patients rushing in for testing, reached out to the College of Pharmacy and College of Medicine in mid-March about setting up a triage site on the UIC Rockford campus.

Together with my College of Pharmacy colleague Annette Hays and partners from the College of Medicine, we assembled a comprehensive plan for triage, testing, and transferring patients that included conferring with county officials as well as local police and fire departments. The assignment represented an interesting turn from my typical duties. Rather than discussing medications, I found myself contemplating issues such as staff and resource management to construct a triage site that could handle upwards of 500 people each day.

With that plan in place, including supplies in hand and tents arranged in the parking lot, we then waited for state or county orders to open the site. The anticipation dragged on me. My wife and I discussed plans for how our family, which includes four children, would deal with the prospect of me living out of a hotel room for an indeterminate number of weeks. Nothing about that would be neat or orderly.

On April 24, the governor ordered the triage site to open, though our anticipated role shifted. The state charged the National Guard to oversee that site and handle all the testing, while my team of pharmacists was assigned contact tracing. Soon after, I helped lead an effort at Crusader Community Health, where I work as a contract clinical pharmacist, to create a similar triage center to accommodate the west side of Rockford. There, I actively swabbed hundreds of patients throughout the summer months. These respective efforts highlight our team’s ability to produce thoughtful plans and rally community partners. Better yet, the framework now exists for us to administer mass vaccinations when a vaccine becomes available.

Though some would suggest the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic has passed, I confess the feelings of unease linger. COVID-19 has not disappeared, and the very real threat of an uptick in positive cases leaves me apprehensive and guarded. Yet, I’m learning to cope with the untidy nature of such anxiety.

As a healthcare provider acutely involved in this process, my duty is to be a voice of reason amid the uncertainty, to share scientific data and display positivity. Recent months have shown me I can reinvent myself in the face of evolving public health needs and be of greater service to my community. And that’s a good drill if, or rather when, something like this happens again.

Alan

Dr. Alan Gross

A clinical associate professor in the Department of Pharmacy Practice, Alan Gross is a clinical pharmacist who specializes in infectious diseases.

Neither healthcare nor pharmacy has experienced anything quite like the COVID-19 pandemic, a once-ina-lifetime event that has challenged us all to go beyond our perceived limits. On a daily basis, our understanding of the disease shifts and new questions emerge. Frankly, we have but one legitimate response: to drive ahead with a relentless focus on patient care.

As COVID-19 began washing over the University of Illinois Hospital in March, addressing this unknown enemy became my singular focus. While our physicians have unique expertise in diagnosis, it stands as a near-impossible effort to comprehensively review every new study, especially against the backdrop of such an intense medical crisis and with an illness as fast-moving as COVID-19. In such an environment, pharmacists play a key role as the drug information experts, and providers looked to me for insights and direction.

I reviewed and evaluated the literature, shared key findings with the healthcare teams, collaborated with pharmacist colleagues, and led the development of treatment guidelines for the swelling number of patients with COVID-19 filling our hospital. As new literature arrived and certain drugs became more difficult to obtain due to shortages, I adjusted plans accordingly and made recommendations for alternative therapies. I wanted to be as flexible and adaptable as possible but, above all, root my work in sound evidence and provide solid, actionable recommendations our teams could execute.

The amount of effort required to combat COVID-19 has been simply incredible. Recent months have given me a deeper appreciation for the critical role everyone on the healthcare team plays—physicians, nurses, and pharmacists alike—and the valuable expertise and perspective we each bring to the table. The word team has never meant so much to me or seemed so vitally important in the healthcare ecosystem.

I believe my hospital colleagues sense that as well, specifically as it relates to pharmacy. I see heightened recognition and greater appreciation for what we have been providing and increased understanding of the meaningful contributions pharmacists make to patient care. With both providers as well as patients, I hope we continue to share that story and demonstrate our value. Every interaction with providers opens the door to building trust and showcasing pharmacists as valuable, skilled partners, while every interaction with patients enables us to explain our role and share our expertise to generate confidence and comfort.

Amid this pandemic, pharmacists have been stepping up, having an even greater presence, and advancing perspectives of their work. Individually as well as collectively, I hope we continue to seize those opportunities moving forward to optimize patient outcomes. Pharmacists can help with the eventual COVID-19 vaccinations, provide education, and serve as a reliable resource for healthcare partners, patients, and the public at large.

As pharmacists, we pledge a lifetime of service to others through our profession. May we all continue to do that with spirit and substance.

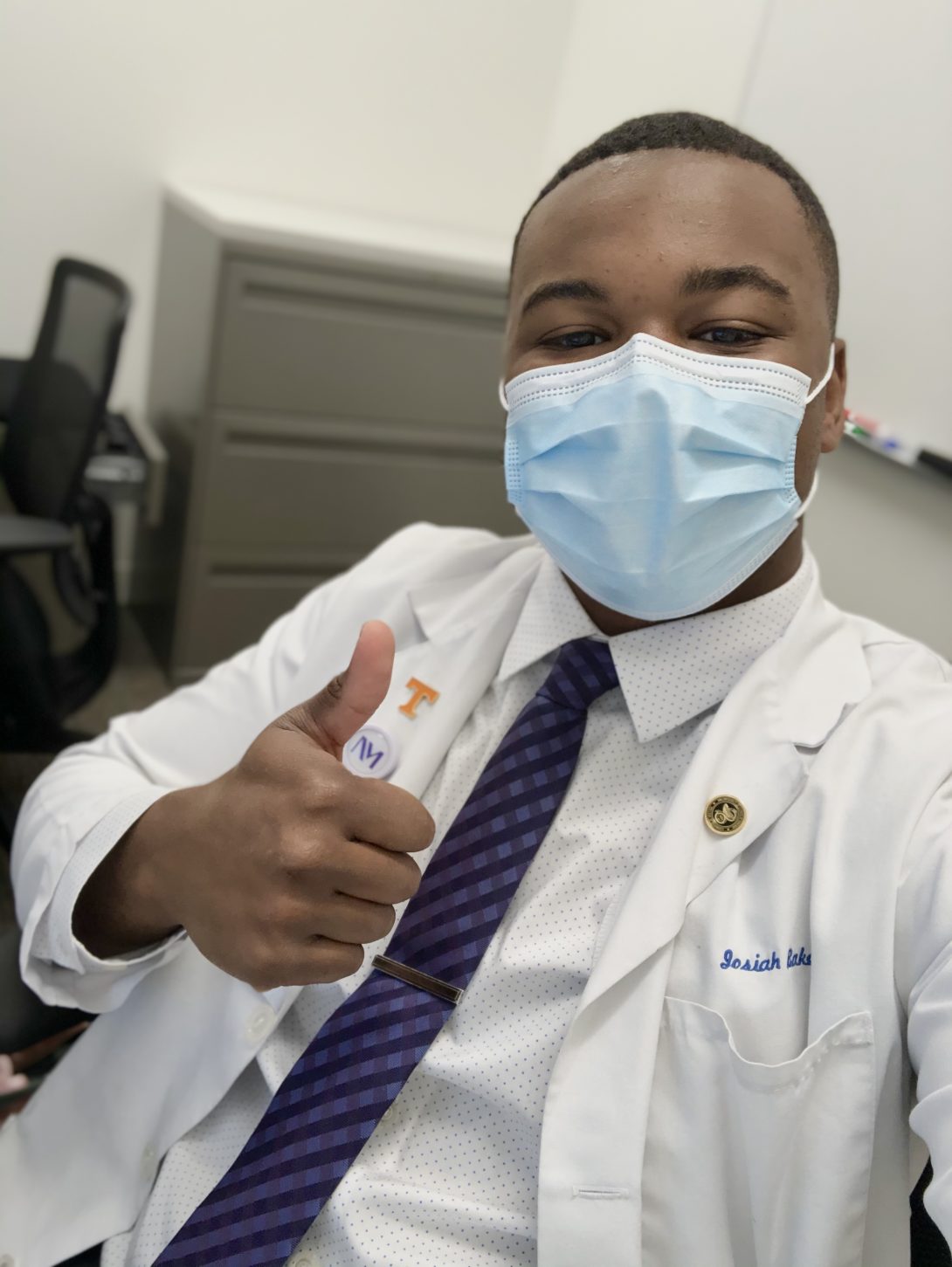

Josiah

Josiah Baker

A fourth-year PharmD student at UIC’s Chicago campus, Tennessee native Josiah Baker works as an inpatient pharmacy intern at Rush University Medical Center and recently completed a one-year term as president of the Illinois Council of HealthSystem Pharmacists’ (ICHP) UIC student chapter.

As early as February, my two roommates and I, all of us UIC PharmD students, were tracking COVID-19’s devastating global developments. Fascinated by the international spread of the novel coronavirus, we had earnest conversations about the ability of the United States’ healthcare system to address the virus and our population’s readiness to acknowledge COVID-19 as a public health emergency very distinct from the common flu. Our shared fear, especially as other nations struggled to contain the virus and care for patients, was that the United States would squander the opportunity to learn from happenings elsewhere. Sadly, our fears turned into reality.

By late March, the typical cadence of my life quickly shifted. Classes and student organization events moved online, clinics closed, and my rotation experience abruptly ended. At Rush, where I primarily conduct medication reconciliations, I switched to interviewing patients over the phone rather than at bedside, eliminating the opportunity to gauge body language, smile, and cultivate an empathetic relationship with the patient.

I also saw fear strike society, as common supplies flew off grocery store shelves and I received a flood of questions from friends and family: What should I do? Is this a hoax? How long might this last? I immersed myself in the literature to be as prepared as possible for those conversations. Others’ accelerating anxiety and their trust in my insights reinforced the concept of being an independent learner and critical thinker, but also compelled me to consider public health’s role in confronting such widespread uncertainty.

It all seemed so unfortunate. And yet when I reflect upon recent months, I consider myself fortunate—an admittedly odd perspective given the upheaval of the COVID-19 era.

Fortunate that I maintained my own health as did many others around me.

Fortunate to have started my first three P4 rotations on site. Heading into these rotations with an open mind and committed to soaking up as much knowledge as I possibly could, I found rich and rewarding experiences that have diversified my skill set—telehealth being one notable example—and expanded my patient care abilities.

And finally, fortunate to have experienced this pandemic as a UIC pharmacy student with access to some of the best hospitals, educators, and clinicians around. I choose UIC three years ago because of its deep focus on patient care and its intense desire to reimagine the traditional role of pharmacists. Throughout this pandemic, I have observed pharmacists push drug development and discovery, clinical innovations, and education, while asserting themselves as medication experts and trusted clinicians whose services save lives and contribute to a more efficient, effective healthcare system. This has emboldened my desire to be a part of patient care and cemented my commitment to the profession.

Here, at the doorstep of beginning my pharmacy career, I find that a particularly fortunate gift.

Tony

Tony Rosella

Tony Rosella is a third-year pharmacy student at the College of Pharmacy’s Rockford campus.

Back in March, I had a seasoned pharmacist tell me that this pandemic would forever influence how I practice pharmacy. Months later, I see the truth in her words and, even more, that this pharmacy path I am pursuing is much more of a calling than I ever realized.

I spent much of the spring navigating two fast-changing worlds: my end-of-the-year course work and my job as a pharmacy technician at SwedishAmerican Hospital in Rockford. As I adjusted to remote learning, a challenge given my extroverted personality and how much I enjoy the in-person classroom experience, I also tracked the evolving environment at SwedishAmerican, which was making swift changes in preparation for COVID-19’s arrival in Rockford. One floor of the hospital became the designated COVID-19 floor. Hospital management shared daily updates about new procedures and protocols. And pharmacists trained in different areas to ensure we would have ample coverage. Amid this, my work hours accelerated to counter the increasing COVID-related efforts, while my job shifted as well. Rather than talking to patients about their medications at bedside, I did so from a hospital phone.

I often found myself wishing I could do more, that I could have a bigger impact on a strained healthcare system. But there are limits to what I, a young pharmacy student, can do. That’s inspired me to prepare for the future.

And it is the future I spend a lot of time thinking about now—at least when I am not fully consumed by present-day demands.

I have thought a great deal about how America and Rockford have responded to this pandemic. While I am proud of my community for their diligent work to increase the safety of everyone, the lack of critical decision-making skills displayed by some troubled me. With so much misinformation about COVID-19 swirling around us, it seems many people struggled to stay adequately informed. This highlighted the importance of public trust in healthcare and has motivated me to consider how I might play a positive role in reducing gaps in knowledge.

It is clear healthcare professionals like pharmacists need to do more community outreach, to provide accurate medical information to people in a clear, unbiased way. I want to be cognizant of building that trust and credibility in my career. Perhaps, it might be something as simple as setting up a vaccine consultation table at community events. There, I could provide information on vaccines, but also offer people a valuable opportunity to talk to a healthcare professional and explain things like medical evidence or the collaboration of healthcare teams.

So, while I am excited to continue my studies, I am most excited to become a pharmacist. This pandemic has already influenced my pharmacy career. It awoke me to pressing issues in the healthcare system and public health at large, and now, more than ever, I feel called to use my license to educate, inform, and support others.

Lisa

Lisa Wendt

Lisa Wendt is currently a P4 student at the College of Pharmacy’s Chicago campus. She works as an inpatient technician at the University of Illinois Hospital while simultaneously sharpening her pharmacy skills at a local CVS outlet.

When I entered pharmacy school three years ago, the term “essential worker” was not as ubiquitous as it is today. And yet, I knew I wanted to be one of those essential workers in healthcare, a needed professional both colleagues and the public at large looked to for help.

Now, after the recent months, we have endured because of COVID-19, I have a renewed sense of what it means to be an essential worker as well as the added purpose behind my actions.

After going about my business as usual—addressing coursework, readying for exams, and training on the hospital’s new computer system, the world around me seemingly changed overnight in mid-March. Classes moved online and the traditional student experience soon followed into the digital world, including the tutoring program I lead at the college and all student organization activities. When I completed my last final in May—also online—I found myself missing the typical postexam lobby gathering with my classmates to discuss finals and celebrate the semester’s completion. It was not the ideal end to the year’s didactic learning, but the college did so well adapting in the moment.

When I received my P4 rotation schedule in April, I hesitated to get too excited. I feared the opportunities I had looked forward to would be drastically different than I imagined. That I was able to begin my first three assigned rotations—first at an oncology clinic in Lincoln Park after Memorial Day before moving onto the UIC Dialysis Center and the University of Illinois Hospital’s Medical Intensive Care Unit—on time and on-site with direct patient interaction was an absolute blessing. I know some of my peers were not so fortunate.

COVID-19 compelled me to reflect on how normalcy exists amid a crisis and how the pharmacist fits into that world. Whenever I changed around the medications typically stocked in the hospital’s MICU to make room for the most in-demand medications needed for COVID-19 patients or sent over-the-counter medications from my CVS store to our COVID-positive patients recovering at home, I felt I was contributing something positive, something valuable. Although simple acts, they were vital.

As I embark upon my final year in the PharmD program and contemplate postgraduation plans, I take the lessons of COVID-19 with me. This pandemic taught me the importance of being flexible, underscored the value of collaboration on healthcare teams, and made me more excited about what pharmacists can offer. I watched pharmacists provide knowledge and perspective. I saw firsthand the impact so many pharmacists had on those they work with, and I gained a deeper understanding of the meaningful role pharmacists play. As these past few months have strengthened my resolve, I realize that the work pharmacists do is not only important, but that it is essential.